Dealing with Bailiffs

Bailiff refused to shod ID or flashed fake police-like ID

Key Takeaways

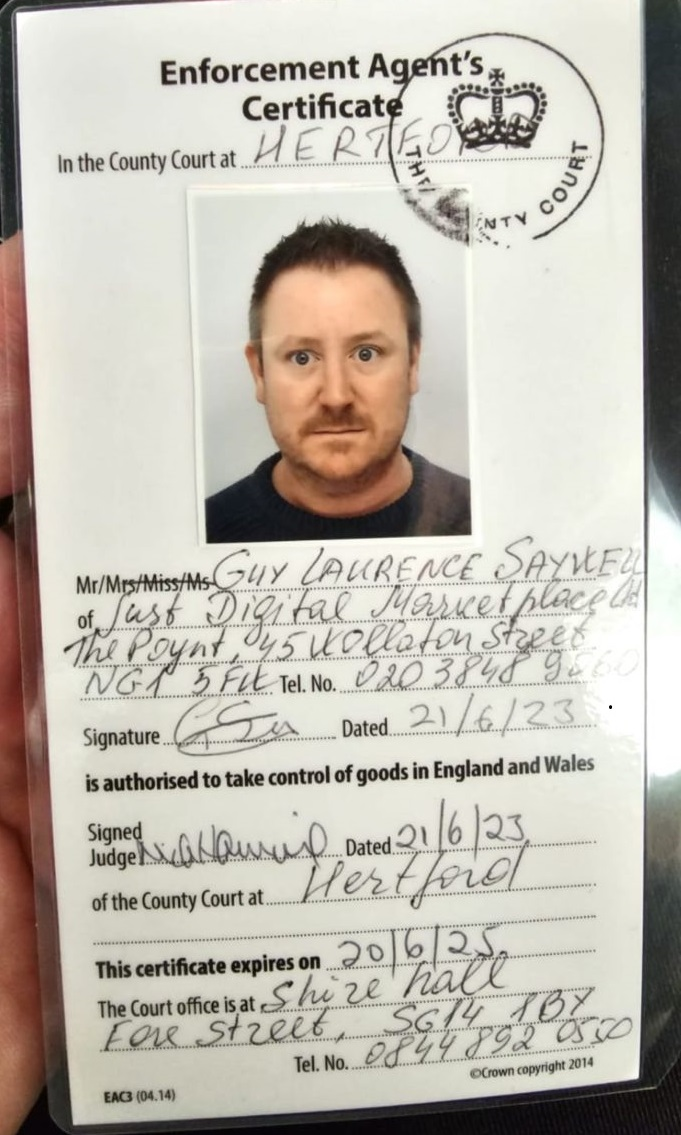

- Enforcement agents must show ID and authority when requested by the debtor or anyone appearing to be in control of the premises

- Valid ID is a white laminated enforcement certificate bearing the agent's photograph and signed by a judge

- Police-style badges or uniforms are not valid identification and may constitute a criminal offence under section 90 of the Police Act 1996

- Enforcement documents must be shown on request and may be presented digitally, with a right to photograph them

- Failure to show authority or ID renders the enforcement unlawful and may give rise to a claim for the return of goods and money under paragraph 66 of Schedule 12

- A bailiff’s court-issued certificate must have a wet-ink judge's signature unlike a Warrant of Control, which may be shown electronically and has no signature

When the Bailiff Must Show Identification

Legal duty to show ID and authority

It is a cardinal principle of lawful enforcement that any individual purporting to exercise the powers of a certificated enforcement agent must be prepared, upon request, to produce clear evidence of both identity and authority. This is not merely a matter of good practice but a strict legal requirement. Paragraph 26(1) of Schedule 12 to the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 imposes an unequivocal duty on the enforcement agent to provide evidence of his authority and identity when requested by the debtor or any person appearing to be in control of the premises. That duty is further reinforced by paragraph 26(2), which clarifies that this obligation may be fulfilled before the attendance or at a later time, thus acknowledging that transparency is not confined to the moment of entry.

What constitutes valid identification

The enforcement agent’s identity must be evidenced by the production of a valid enforcement certificate. Pursuant to section 64 of the same Act, this certificate is granted by the County Court following a rigorous application and vetting process. The certificate is typically presented as a white laminated card, approximately six inches by two and a half inches in dimension, bearing the agent’s photograph and the signature of the issuing judge. It is the sole authoritative evidence of a person’s status as a certificated enforcement agent. Any substitute such as a branded badge, company uniform, or the display of a police-style warrant card does not satisfy this statutory requirement and risks misleading the public. Where such misleading conduct occurs, particularly the impersonation of a police officer or the use of insignia likely to cause such confusion, the enforcement agent may commit a criminal offence under section 90 of the Police Act 1996.

Genuine: court issued enforcement certificate signed by a judge

Fake: police style badge or ID is not valid enforcement identification

Evidence of authority to enforce

The same statutory scheme obliges the agent to exhibit their authority to enforce, which is typically in the form of a warrant of control, a High Court writ of control, or in other cases, a council tax or business rates liability order. While the law does not require these documents to bear a wet-ink signature, their authenticity must be apparent. A common practice is to display the warrant or writ on a digital device such as a tablet. In such cases, the person affected is lawfully entitled to inspect it and to photograph it for the purposes of verification. It is entirely proper for the person at the premises to ask the enforcement agent to remain outside while the document is checked, particularly if there is doubt as to the address or the amount claimed. This check is an essential safeguard given that enforcement documents are frequently defective or issued in error.

Consequences of refusing to show ID or authority

It must be emphasised that the mere assertion by an enforcement agent of authority is legally insufficient. Authority must be evidenced. Where no valid document is produced, or where the agent refuses to present it, any entry or seizure of goods may constitute unlawful interference. This is particularly important where enforcement action involves vehicles clamped or removed from the public highway, often through automated number plate recognition. In such cases, agents routinely avoid presenting the underlying authority, often because the warrant does not specify the correct location or because there is no lawful basis to treat the vehicle as subject to enforcement. The failure to produce valid authority in such circumstances is not a technical omission. It is a fundamental breach of the statutory scheme.

Remedies for unlawful enforcement

Where the enforcement agent fails to comply with these duties, the person affected has a right of redress. Paragraph 66 of Schedule 12 permits an application to the court for the return of controlled goods and the repayment of any money unlawfully taken. This remedy is available not only to the debtor but to any person whose goods have been interfered with or who suffers loss as a result of the enforcement breach. Such applications are commonly supported by video recordings or contemporaneous evidence, which the courts accept as probative where they illustrate that no identification was produced or no authority shown. Moreover, if the enforcement breach is particularly egregious or deliberate, the court has discretion to make an order for the payment of legal costs and compensation.

Conclusion and next steps

In sum, a bailiff’s power exists only where it is lawfully conferred and transparently exercised. The duty to show identification and authority is a legal requirement, not a discretionary courtesy. Any failure to do so vitiates the enforcement action and opens the agent and the instructing creditor to judicial scrutiny, civil liability, and in some cases, criminal prosecution. Those affected should take prompt steps to preserve evidence, seek legal advice, and bring the matter before the court in the form of a statutory challenge or damages claim as appropriate.

Remedies

- Claim legal costs where the court finds the agent's conduct to be unreasonable, unlawful, or deliberate

- Gather and submit video evidence or photographs showing that no valid ID or fake ID was presented

- Report use of false police-like ID to the police under section 90 of the Police Act 1996 or section 7 of the Fraud Act 2006

In sum, a bailiff's power exists only where it is lawfully conferred and transparently exercised. The duty to show identification and authority is a legal requirement, not a discretionary courtesy. Any failure to do so vitiates the enforcement action and opens the agent and the instructing creditor to judicial scrutiny, civil liability, and in some cases, criminal prosecution. Those affected should take prompt steps to preserve evidence by recording the encounter, requesting copies of any warrants shown, and seeking legal advice at the earliest opportunity. If there is any doubt as to the lawfulness of the enforcement action, the person concerned should apply to the court for appropriate relief, including the return of goods, reimbursement of funds taken, and where appropriate, an injunction to prevent further unlawful conduct.